Lightning strikes set patches of forests and prairies afire at frequent intervals for almost 10,000 years. And for centuries, Native Americans lit grass fires regularly to expand and maintain the prairies, which helped the fire-adapted native grasses thrive and feed their main source of food, the massive bison herds.

And in addition to the frequent fires, native peoples, and millions of bison, there was one prairie insect whose influence was also felt landscape-wide -- the inch and one-third long, Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus).

And in addition to the frequent fires, native peoples, and millions of bison, there was one prairie insect whose influence was also felt landscape-wide -- the inch and one-third long, Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus).

The difference between grasshoppers and locusts is behavior. When they occur in non-damaging, non-migrating, low-density, widespread populations, they are grasshoppers. They are locusts when they form damaging, concentrated, migratory populations.

When Lewis and Clark were migrating across the northwest, there were roughly 30-60 million bison in North America. Seventy years later, the locust population was peaking at around 15 trillion insects at the same time that those 11 million tons of bison were getting slaughtered by commercial hunters and government agents. Soon, at 8.5 million tons, locusts outweighed bison.

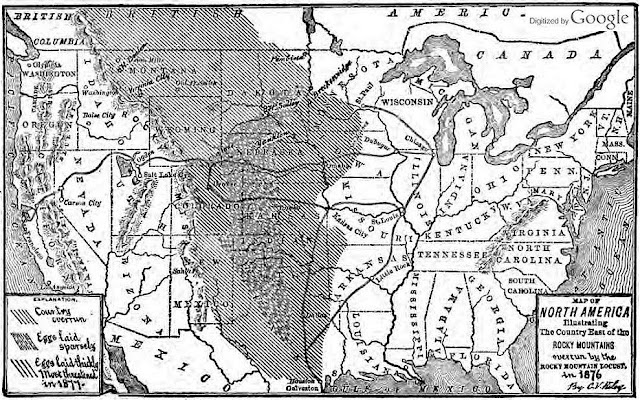

The Guinness Book of World Records lists locust swarms as the "greatest concentration of animals." One swarm covered 198,000 square miles -- Montana is a little over 147,000 square miles. Europeans settling in the Montana Territory endured repeated locust swarms, which peaked in the pre-statehood years between 1873 and 1877.

And then, in less than 25 years, North America's only major locust suddenly vanished. Everywhere. "The First Annual Report of the State Entomologist of Montana" in 1903 declared that Rocky Mountain Locusts, "...if present in the state at all is very rare." They had no way of knowing that the last living locust had died a year earlier.

What happened?

Summer 1868. A locust swarm in the vicinity of Helena, "came in from the north, ...striking the buildings on the south side of the street, and fell down in such large numbers as to form 'drifts of 'hoppers.'" One man in Helena said there were so many locusts that, "... while driving oxen he 'couldn't see the front yoke.''

March 1877. The U.S. Entomological Commission was created to "...prevent this fertile country from being overrun by the disastrous winged swarms from the Northwest."

August 1878. A company of army troops moving through Milk River area reported, "...the appearance of vast swarms of locusts... coming and going for more than one week. ...Some of the men with whom I spoke say that the roar of their wings was much like the sound of a tornado."

August 1879. The U.S. Entomological Commission reported, "During the summers of 1874, 1875, as well as 1878, the locusts were so numerous at Bozeman that they entered stores and eat [sic] holes in the various kinds of goods."

Spring 1887. In the Sun River Valley, "the young [locusts] were so numerous that the ground was completely hidden by them in many localities."

Settlers flooded westward only to find unpredictable waves of locusts swarming east and south -- and a battle for the Great Plains was set into motion. Hungry locusts devoured almost all vegetation in their path, including many of Montana's first fields of wheat and grains. (Oddly, they avoided tomatoes, raspberries, and alfalfa.) They also ate fence posts, clothing, bark, leather, and wool still on the sheep.

Settlers flooded westward only to find unpredictable waves of locusts swarming east and south -- and a battle for the Great Plains was set into motion. Hungry locusts devoured almost all vegetation in their path, including many of Montana's first fields of wheat and grains. (Oddly, they avoided tomatoes, raspberries, and alfalfa.) They also ate fence posts, clothing, bark, leather, and wool still on the sheep.

Starving settlers fought back by burning, poisoning and flooding -- all to little success. Religious leaders proclaimed that the locusts were sent to punish settlers for their sins, and they prayed and performed exorcisms to banish the insects -- also to little success. Locust swarms tormented the settlers for more than 30 years.

But then suddenly, at the turn of the century, locusts vanished for mysterious reasons. One hundred years later, in 2004, a Wyoming scientist finally put the clues together and solved the cold case of the disappearing locusts.

Locusts were quickly plowed into extinction -- literally -- when western farming practices collided head-on with the insect's own natural history.

The Rocky Mountain Locust swarms were occasional and erratic. Between irruptions, the population fell back to much smaller levels -- perhaps as few as 10 million locusts -- in areas along the eastern flanks of the Rocky Mountains. While great swarms afflicted the prairies, the core population existed almost exclusively in arable lands along streams -- land that was good for farming.

Farmers moved in and unknowingly (at first) began plowing these same locust core areas for their crops.

Farmers moved in and unknowingly (at first) began plowing these same locust core areas for their crops.

Reports of farmers finding locust eggs by the thousands were common. When they turned the soil, they exposed the buried locust eggs to Montana's freezing temperatures. When surviving eggs hatched upside-down in the sod, many hatchlings were too deep to surface and too small to negotiate the broken clumps. And when farmers started planting alfalfa, which requires a lot of water, they grew a non-native crop that was apparently not eaten by locusts, and one that created a moist habitat where locusts could not survive.

Native locusts were driven to extinction. Bison narrowly avoided the same fate. Native Americans were intentionally starved and forced onto reservations. Wild fires were fought with little regard for their beneficial effects. And underneath it all, the native prairies were reduced to isolated patches that total less than 1% of what once existed.

But today, the Rocky Mountain Locust is rising once again -- sort of.

In the Beartooth Mountains of southwestern Montana, there lies the remains of the aptly-named "Grasshopper Glacier." (Actually, there are two "Grasshopper Glaciers" and one "Hopper Glacier.") Apparently, when swarms of the migratory locusts flew over the mountain range, many were caught in storms or otherwise perished, and were buried in accumulating snow and ice.

"Grasshopper Glacier" was four miles long in 1914, but now it's only one-quarter of that size. Thanks to the effects of global warming, melting ice is now slowly revealing its cache of millions of long-dead locusts that lived in decades past.

Read more: Why locusts swarm

Behind the bug: You can read all about the Rocky Mountain Locust in professor Jeffrey Alan Lockwood's book, "Locust: The Devestating Rise and Mysterious Disappearance of the Insect That Shaped the American Frontier." If you're into 500+ page government reports, you can download the "Third Report of the United States Entomological Commission" (the most interesting one) at: http://books.google.com/books.