(Extra-long edition covers multiple holidays...)

|

| Comet Lovejoy rises over Glacier Park's Mt. Brown on Dec. 7th, 2013 |

Long ago, before the first Christmas as we now know it, good people of the northern hemisphere looked forward to a late-December celebration.

Winter solstice, the shortest day of their year, was celebrated in myriad ways among countless cultures.

When the winter solstice fell on December 25th, in 274 AD, Roman Emporer Aurelian proclaimed the day as "

Natalis Solis Invicti," the "festival of the birth of the invincible sun." Many years later, Christians would borrow this date for a new celebration of love, joy and hope.

This year, the winter solstice arrives today, December 21st. Four days before Christmas, two weeks after Hanukkah ended, and a month after the aptly-named "Black Friday." But so far this month, it has been Comet Lovejoy - not Santa Claus, Hanukkah Harry or Sam Walton - that has delivered excitement, inspiration and amazement the world over (unlike that Grinch, Comet ISON).

Lovejoy showed up unannounced in the middle of these celebrations. What about hope? Well, that's a different story. Hope takes us back a few decades, back to the 1910 return of Halley's Comet. But first, hope had to endure centuries of fear and ignorance - the twin currencies of soothsayers then and now.

Movements of the sun and moon were regular and predictable to even the earliest peoples, but comets appeared and disappeared without warning, which made comet sightings scary to some. Looking backwards in time, some people began to associate comets with any event that had also occurred at roughly the same time - a few peaceful events, but mostly destructive ones - casting comets as bad omens.

Admittedly, the science side of comets also got off to a rocky start with "Aristotle's Comet" in 372 BC (when the wise young Greek was but 12 years old), partly because the first telescopes were still 2000 years in the future. So as an adult, even Aristotle mistakenly described comets as Earthly gasses which, after rising to the upper atmosphere, were set afire by friction from

the heavens revolving around us. A quick flame produced a shooting star, a slow flame produced a bright comet.

A set of Chinese silk paintings from 168 BC was a field guide to comet tails, identifying whether war, famine or death would soon follow. A comet appearance in 74 BC was later hitched to the fall of Jerusalem in 70 BC, four years after the comet passed. And 1st century Roman poet/astrologer,

Marcus Manilius, wrote of comets in

Astronomica (a single poem that filled five volumes),

"Heaven in pity is sending upon Earth tokens of impending doom." It started sounding like the heavens were sending more doom than hope.

|

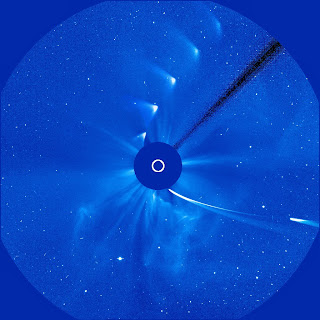

| Halley's Comet in Gitto's "Adoration of the Magi" |

Maybe the best, rare good omen was the return of Halley's Comet in 1301, serving as the inspiration behind a blend of religion and comet lore. In "

Adoration of the Magi," the famous fresco completed in 1306 by Italian painter Giotto di Bondone, a comet replaces the Star of Bethlehem above the adorers who are kissing the feet of baby Jesus. In composing his version of the nativity scene, Gitto replaces the guiding angels with a comet. It stands well apart from other religious art masterpieces created in that time.

Returning to bad omens, two comets in 1664 and 1665 became superstitiously linked to the 1665 Black Plague of London (which actually originated in the Netherlands in the 1650's). That same year, an English astrologer published

De Cometis, warning that,

"These Blazeing Starrs! Threaten the World with Famine, Plague, & Warrs" [sic]. No doubt his book became a best-seller - at least among the frightened survivors.

How does this business of

misinformation lead us to hope? Don't worry, we're getting there.

It began in 1682 when English astronomer

Edmond Halley began studing the motion of comets, after witnessing two of them in person. Using a

revolutionary new theory of gravity, from the "

Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica," published in 1687 by Sir Isaac Newton (following Halley's considerable encouragement and support), Halley predicted that this comet was the same one recorded in 1531 and 1607, and that it would return again in 1758. Unfortunately, Edmond Halley died in 1742. But in 1758, the comet re-appeared exactly as Halley had calculated - the date was Christmas Eve.

Haley's Comet only comes 'round once every 74 to 79 years (the timing gets altered by gravity from the planets it flies past). It's next appearance will occur on July 28th, 2061. Back in 240 BC, Chinese astronomers noted a bright comet, which is the earliest accepted record of what we now call Halley's Comet. Since then, this singular comet has been blamed for an astounding array of events.

The comet named after a brilliant scientist was also blamed by some people for the 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius and the destruction of Italian city of Pompeii. His comet of 1066 was taken as a sign that the English would be defeated by invading Normans at the Battle of Hastings. And Halley's Comet in 1835 was especially busy, catching blame for the fall of the Alamo in Texas, a New York City fire that burned 530 buildings, and for starting wars in Cuba, Mexico, Ecuador, Central America, Peru, Argentina, and Bolivia!

In spite of so much superstition - and also because of it - the return of Halley's Comet in 1910 finally brought hope. Literally, at first.

Hope first arrived in pill form - specifically, "

Hope's Anti-Comet Pills," which were advertised as, "

An Elixir for Escaping the Wrath of the Heavens." Thousands were sold for 25 cents to one dollar apiece, depending on the customer's anxiety level. (The pills were a harmless combination of sugar and quinine.)

As Earth anxiously approached Halley's dusty trail in May of that year, the hucksters turned out in force. In addition to anti-comet pills, you could purchase lead umbrellas that would deflect deadly comet dust. Or you could rent a seat on a submarine that would remain safely submerged while everything on land was destroyed in a fiery inferno.

Or, if you lived in south Texas, you could buy comet-proof leather inhalers for between $2 and $24, sold by two busy entrepreneurs from Ohio. Both men were arrested for swindling, but the Brazoria County Courthouse was besieged by crowds of Texans who pleaded for the men to be released. Successful, some of these panicked people then purchased 50 inhalers at a time.

Churches were packed across the US. In Philadelphia, the Rev. Abraham Lincoln Johnson held a revival that reduced his congregation to a "paroxysm of fear" as he described the coming comet destruction. A California prospector nailed his own feet and one hand to a cross, then pleaded with his rescuers to leave him be. A Louisville newspaper reported on end-of-the-world preparations "through central and eastern parts of Kentucky."

|

| Halley's 1910 Comet was the first one ever photographed |

Around the world, the money changers profited from the many souls preparing for doomsday. And yet...

Among other parts of the populace, rooftop comet-viewing parties were lavishly arranged and heartily enjoyed because, as you may know, as the human race passed through the dust trail of Halley's Comet for

six full hours, every person who had swallowed Hope Pills survived unscathed - and so did everyone else. Their celebrations were accompanied by dance music from a popular song sheet, the "Halley's Comet Rag," and comet post cards and souvenirs sold quite well in Paris.

Unlike earlier comet viewers, the good people of 1910 Earth had newspapers, telegraphs and telephones that quickly spread the lack-of-destruction news between distant lands. Hucksters made use of these new technologies, of course, but so did scientists and reporters. And in this way, an infant, world-wide public relations event was born.

The fear mongers faded back into the shadows, and the big 1910 comet celebration turned into a public and scientific hit!

It was an educated man who predicted the "Broom Star's" return in 1910. It was men of reason who assured and reassured that the comet posed absolutely no threat to any Earthly life form. And it was a good portion of the general public who finally began putting their some of their faith into reason, probably for the first time ever on a world-wide basis. This was a huge victory for science, a slam-dunk defeat over the purveyors of fear and ignorance, and the good people took notice.

Reasoned hope was a true blessing that we received, belatedly, in 1910.

Widespread fear of comets disappeared for the rest of the 20th century. Unfortunately, like a scary-good zombie, a profitable business model is also hard to kill, regardless of the damage it may cause. And so fear is becoming a hot commodity once again. Fear can be a formidable foe, if you allow it, but reality is undefeated in the end. So whenever I hear these modern-day soothsayers (anti-vax, climate change deniers, etc.) selling fear, ignorance and hate as alternatives to love, joy and hope, I just smile and think to myself,

COMET PILLS !

Comet Lovejoy makes its closest approach to the sun tomorrow, December 22nd, and from there it will get slung back out into our night skies for a little while longer. This holiday season, I hope that you can take time to appreciate

all manner of heavenly gifts that are offered. Happy belated Hanukkah, peaceful solstice, and merry Christmas!

COMET MUSIC: Even if there was more than one modern song written about comets (there isn't), my favorite would still be, "Halley Came to Jackson," written and performed by Mary Chapin Carpenter here. You can read all of the lyrics here.

Late one night when the wind was still, Daddy brought the baby to the window sill

To see a bit of heaven shoot across the sky, The one and only time Daddy saw it fly

It came from the east just as bright as a torch, The neighbors had a party on their porch

Daddy rocked the baby, Mother said "amen," When Halley came to visit in nineteen ten

(from "Halley Came to Jackson" by Mary Chapin Carpenter)