He pointed me to a website that shows several years of data from 50 Tundra Swans that were outfitted with satellite transmitters. While my own map showed one arrow for one pair of banded swans, the Alaska Science Center website shows the same map covered with a spaghetti bowl of swan migration routes - pretty cool!

|

| USGS map showing migration routes of 50 Tundra Swans. |

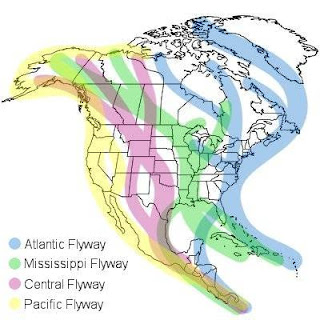

As recorded by satellite, the daily movements of Tundra Swans through Montana during fall migration is a surprisingly consistent, smooth arc curving towards north central California. All of these swans flew down the east side of the Continental Divide, and many appeared to be out over the plains, slightly east of the Rocky Mountain Front.

Spring migration back north was a little different, even though it involved the same birds. First off, several swans flew up the west side of the Continental Divide, through western Montana. And the swans that flew back up the east side of the Divide were closer in to the mountains, not over the plains. These swans were using two different migration flyways during each migration. From Alaska to Montana, they were in the Central Flyway. But then they turned towards California and entered the Pacific Flyway.

Spring migration back north was a little different, even though it involved the same birds. First off, several swans flew up the west side of the Continental Divide, through western Montana. And the swans that flew back up the east side of the Divide were closer in to the mountains, not over the plains. These swans were using two different migration flyways during each migration. From Alaska to Montana, they were in the Central Flyway. But then they turned towards California and entered the Pacific Flyway. This is when I start rubbing my chin. Hmmm. These different migration patterns are very interesting. But what gets my attention is that every single one of the marked Tundra Swans that migrated through Montana - what we like to call "our swans" - wintered in north central California.

Central California. The infamous Central Valley, where 8% of U.S. crops are produced on just 1% of U.S. farmland by heavy use of irrigation, pesticides and fertilizers. Agricultural runoff and selenium pollution have already lead to the collapse of some Central Valley fisheries, and to some large-scale bird die-offs.

Now, through the magic of satellite telemetry, I can see that many Central Valley birds are also "our" Montana birds, our Tundra Swans. Before seeing this migration map, I had never connected the dots.

Alaska, Canada and Montana are still fairly pristine. But the future of many if not most Tundra Swans in this vast region hinges on the pollution control - or lack thereof - in a relatively small part of California.

To end on an upnote, a red-banded Trumpeter Swan turned up last week during our weekly MT Fish Wildlife & Parks waterfowl survey. The lone swan, banded 7T1, was resting and feeding on Smith Lake west of Kalispell. He/she was born in 2008 and was banded in 2009 just south of Polson by Dale Becker - a biologist with the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes who also happens to be the President of the Trumpeter Swan Society. The Tribes have been reintroducing Trumpeters to the reservation since 1996. Polson is a one-hour drive due south from where we observed the banded bird. We saw a red-banded swan near Smith Lake last spring, too, but we were never able to get close enough to read the band code.

To end on an upnote, a red-banded Trumpeter Swan turned up last week during our weekly MT Fish Wildlife & Parks waterfowl survey. The lone swan, banded 7T1, was resting and feeding on Smith Lake west of Kalispell. He/she was born in 2008 and was banded in 2009 just south of Polson by Dale Becker - a biologist with the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes who also happens to be the President of the Trumpeter Swan Society. The Tribes have been reintroducing Trumpeters to the reservation since 1996. Polson is a one-hour drive due south from where we observed the banded bird. We saw a red-banded swan near Smith Lake last spring, too, but we were never able to get close enough to read the band code.