|

| A middle-aged yellowbell with alongside purple shooting stars blooming this week in a ponderosa pine forest near Polson |

Showing posts with label Lewis and Clark. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Lewis and Clark. Show all posts

Wednesday, April 29, 2015

Modest Mission Bells

Thursday, June 12, 2014

"The Grandest Sight I Ever Beheld"

|

| Swallows forage in the swirling air currents of Rainbow Falls in early June on the Missouri River |

Two hundred and nine years ago today, a small group of explorers on foot clambered upon a series of five waterfalls in central Montana.

They were the first white guys to see these thundering falls that the local Blackfeet residents had known for generations. Even the Mandan, living weeks downstream in North Dakota, had told the party of explorers about "Minni-Sose-Tanka-Kun-Ya," the great falls. Still, the explorers could hardly believe their eyes, and their chief scribe had a hard time describing the scene in his journal.

"I hurryed down the hill which was about 200 feet high and difficult of access, to gaze on this sublimely grand specticle. ... immediately at the cascade the river is about 300 yds. wide; about ninety or a hundred yards of this next the Lard. bluff is a smoth even sheet of water falling over a precipice of at least eighty feet, the remaining part of about 200 yards on my right formes the grandest sight I ever beheld, the hight of the fall is the same of the other but the irregular and somewhat projecting rocks below receives the water in it's passage down and brakes it into a perfect white foam which assumes a thousand forms in a moment sometimes flying up in jets of sparkling foam to the hight of fifteen or twenty feet and are scarcely formed before large roling bodies of the same beaten and foaming water is thrown over and conceals them."

"I most sincerely regreted that I had not brought a crimee [camera] obscura with me by the assistance of which even I could have hoped to have done better but alas this was also out of my reach; I therefore with the assistance of my pen only indeavoured to traces some of the stronger features of this seen by the assistance of which and my recollection aided by some able pencil I hope still to give to the world some faint idea of an object which at this moment fills me with such pleasure and astonishment, and which of its kind I will venture to ascert is second to but one in the known world."

- Meriwether Lewis

- Meriwether LewisJune 13, 1805

The expedition had expected a half-mile portage around the falls. What they found instead was a month-long, 18-mile portage that included incidents with grizzly bears, a wolverine, mountain lion, three ornery bison bulls, lots of rattlesnakes, countless prickly pear and mosquitoes stabbing them, and torrential downpours with large hail. Welcome to summer in Montana...

Labels:

Lewis and Clark,

MT History,

MT Places

Location:

Great Falls, Mount, MT, USA

Friday, May 31, 2013

The Bitterroot Backstory

|

| Rare, white bitterroot flowers |

Native American names for this diminutive plant include, "Spetlum" and "Nakamtcu." Countless generations of native women have headed into the mountains in early spring to dig and collect the roots, after the plants had grown leaves but before blooming. Today, tribal elders still pass along the centuries-old knowledge that spring bitterroots are the most nutritious, and that the roots grow even more bitter after flowering. And though they were not lost, Montana's natives and bitterroots were both "discovered" by a distant nation intent on expansion - the young United States.

The "undiscovered," western bitterroots were blooming in May and June, 1803, when the east coast's President Thomas Jefferson sent his personal secretary, a distant relative named Meriwether Lewis, to learn botany from Benjamin Barton. Lewis would spend the better part of three years learning botany, map-making, mathematics, anatomy, fossils and medicine from the top American scientists of the day. All of this was preparation for a two-year journey we now call, "The Corps of Discovery."

To assist in this journey, Lewis selected his former commander in the U.S. Army, William Clark. Lewis and Clark and crew traveled the northwest from May 1805 until September 1806, collecting plant and animal specimens, meeting with Native Americans, and mapping the uncharted mountains and rivers - while also serving Jefferson's primary goal of pre-empting the French and Spanish by staking a U.S. claim to northwest territory, which lay west of his new "Louisiana Purchase" lands.

On April 29th, 1805, the Corps of Discovery camped near present-day Fort Peck, having entered into what would eventually become Montana Territory the state of Montana. It was four months later, on August 22nd, when Lewis mentioned the bitterroot plant in his journals for the first time. The corps was camping just west of the continental divide separating modern-day Montana and Idaho. Lewis' initial report is credited with giving this plant it's common name:

"another speceis was much mutilated but appeared to be fibrous; the parts were brittle, hard, of the size of a small quill, cilindric and as white as snow throughout, except some small parts of the hard black rind which they had not seperated in the preperation. this the Indians with me informed were always boiled for use. I made the exp[e]rement, found that they became perfectly soft by boiling, but had a very bitter taste, which was naucious to my pallate, and transfered them to the Indians who had eat them heartily." (August 22nd, 1805)

The only other time Lewis mentioned bitterroot plants in his journals was on July 2nd, 1806, during their return trip from the Pacific Ocean. It was on this date that Lewis collected his first bitterroot specimens, in the area known as "Travellers' Rest," near present day Lolo. Lewis didn't elaborate much:

"I found several other uncommon plants specemines of which I preserved." (July 2nd, 1806)

Lewis' plant specimens were sent back to Jefferson at various times, with the first batch arriving in August, 1805 - almost a year prior to Lewis collecting the bitterroot specimens. The president himself dried the plant specimens and sent them on to Barton, the botanist who had trained Lewis.

Can you even imagine a modern president - or any politician at all - having the knowledge and interest to properly prepare pressed plant specimens? Jefferson was a curious and complicated intellectual, and it was his unusual interest in botany that boosted the bitterroot's backstory.

Jefferson expected Benjamin Barton to describe and catalogue Lewis' plant collection. Jefferson's confidence in Barton, however, was misplaced. While Barton was a top botanist, he also had a long history of not completing projects that he started. Though he'd studied at the University of Edinburgh, Barton returned to the U.S. without a university degree. This didn't prevent him from becoming an academic, lecturing in medicine, natural history and botany. Embarrassed by his lack of credentials, Barton purchased a "Doctor of Medicine" degree 10 years before tutoring Lewis.

It so happened that, as Lewis' plant specimins began arriving in 1805, Barton hired a young Frederick Pursh to work as his part-time plant curator. Two years later, in April, Meriwether Lewis personally met with Pursh in Philadelphia to guide him in preparing a catalogue of the expedition's plant collection. Pursh began working on the project that winter.

Pursh's part-time employment provide for his two weaknesses, wonderlust and alcohol. In 1805 and again in 1806, he set out on foot with his dog to collect plants and ended up exploring over 3,000 miles on each trip. While at work, however, Pursh soon grew disenchanted with Barton, who failed to provide him with enough money to live on. Parsh was also worried with the thought that Barton would get all of the credit for his hard work if and when Lewis' catalogue was published. It didn't help matters that Pursh was also fighting a lifelong battle against serious alcoholism.

Pursh soon left his position with Barton for a job in New York, then moved to London in 1811, taking most of Lewis' priceless, American plant collection with him. While living in London, Pursh created rancor in the scientific community by publishing Flora Americae septentrinonalis ("Flowers of North America") in 1813, describing 134 of Lewis' plant specimens including, on page 368, one by the name of "Lewisa rediviva Pursh" - the bitterroot. The book was only a modest success.

Pursh soon left his position with Barton for a job in New York, then moved to London in 1811, taking most of Lewis' priceless, American plant collection with him. While living in London, Pursh created rancor in the scientific community by publishing Flora Americae septentrinonalis ("Flowers of North America") in 1813, describing 134 of Lewis' plant specimens including, on page 368, one by the name of "Lewisa rediviva Pursh" - the bitterroot. The book was only a modest success.

A few years later, on July 11th, 1820, Pursh died drunk and destitute in Montreal. He never returned the American plants to Lewis, maintaining the division he had created. After his death, botonists gave him a dubious honor by naming a family of plants after him - the "bitterbrush" (Purschia).

In his book, Pursh identified the bitterroot as both a new genus and a new species. He gave it the genus name, Lewisia, to honor the collector. The species name, redivivia, comes with its own backstory. It translates as, "back to life," in reference to a dried root collected by Lewis that sprouted leaves when Pursh planted it in his Philadelphia garden. The resuscitated plant never bloomed for Pursh. Although he had never seen a bitterroot flower first-hand, Pursh made a pretty accurate drawing of the plant based on Lewis' descriptions.

|

| Pursh's bitterroot drawing |

During the late 1800's, the Women's Christian Temperance Movement (WCTM) formed in Ohio to create a "sober and pure world." The movement expanded its membership by advocating for each state to designate an emblematic flower. In 1891, delegates to the Montana chapter of the WCTM changed their earlier choice and suggested that the bitterroot should become Montana's official state flower.

The process turned formal In January of 1894, when a Bozeman journalist, Mary Alderson, formed the Montana Floral Emblem Association (now known as, Montana Federation of Garden Clubs). Most major towns formed county and community committees to debate which native flower Montana should choose. The issue turned into one of Montana's first state-wide referendums, ushering in a new direction of progressive politics in the state.

The debate spilled over into the pages of local newspapers. Columns described the candidates, and editorials advocated for this or that flower. An 1894 editorial in the Helena Independent argued that the bitterroot, "has one quality which should be fatal to it as a state emblem. It has no stem...." Without a stem, they decried, the bitterroot couldn't be worn as a boutonniere or made into a bouquet.

To settle the matter, ballots were sent out and voting was concluded on September 1st, 1894. A total of 5,857 votes were cast for more than 32 different flowers. The bitterroot won hands down, with 3,621 votes. Evening primrose came in a distant second (787 votes) and the wild rose landed in third place (668 votes). The bitterroot only grows in western parts of Montana, but it won in 10 of the 15 counties that voted.

And so it came to be that on February 27th, 1895, the Montana state legislature designated the bitterroot as our official state flower, without a single dissenting vote.

Behind the bitterroots: I haven't read it yet, but one of the last of the old-time Rangers in Glacier Nat. Park, Jerry DeSanto, filled an entire book with the backstory on bitterroots. "Bitterroot: Montana State Flower" is now out of print, but you can still finds copies floating around if you look hard enough. Anything written by one of the old-school guys should be an interesting read.

|

| Bitterroot in bloom (c) John Ashley |

Labels:

Bitterroot,

Lewis and Clark,

MT History,

Plants,

Wildflowers

Saturday, August 18, 2012

Summer's Berry Bounty

"We feasted sumptuously on our wild fruits, particularly the yellow currant

and

the deep perple serviceberries, which I found to be excellent."

(Meriwether Lewis, August 2nd, 1805)

|

| Cedar Waxwing and purple serviceberries |

Or depending on where you live and who raised you, you might call them Juneberries (eastern Montana), Saskatoons (Canadian Rockies), shadberry (northeastern US), sarvisberry (Wyoming), or simply pomes (boring botanists).

Call it what you will, but it is one of our most sought-after berries by people and animals alike.

Native Americans used serviceberries as an ingredient in pemmican, and some tribes also dried and pounded them into fruit patties weighing 10-15 pounds each. Lewis and Clark reported their encounter with sweet serviceberries more than 200 years ago, from somewhere near the current town of Whitehall.

If you're so inclined, pick some soon because the competition is everywhere. Bears and birds both savor the ripe summer serviceberries, while the stems and leaves are eaten by elk, deer, moose and bighorn sheep.

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

Montana's Last Wild Mustangs

|

| Pryor Mountain Wild Horse Range in SE Montana |

It’s a long story, a story that -- in many ways -- is interwoven with the fates of 80 million native people already living in the Americas when Europeans arrived.

Horses evolved in North America (NA) about 55 million years ago, and eventually expanded into Europe by crossing the Bering land bridge. About 10,000 years ago, Paleo-Indians crossed the same land bridge and spread east and south into NA and, within 2,000 years, horses were extinct here on their native continent. (The charred bones of native NA horses, camels and mastodons would later turn up in cooking pits excavated by modern paleontologists.)

Horses were missing from NA for 8,000 years, while some bands in Europe were caught and domesticated. Starting with Columbus’ second voyage in 1493, Spanish explorers brought horses back to NA. As these domesticated ponies escaped or were stolen and traded by the Native Americans, bands of free-ranging horses quickly re-established across much of western NA. Back on their native soil, horses would soon find themselves targeted for extinction once again, this time by the corporate ranching industry, which wanted (and still wants) control over all public grass and public lands to fatten up their bred-down cattle.

******************************************

The oldest known ancestor of the modern horse was a 4-toed, 80-pound animal named “eohippus.” At that time, the lands we now call NA and Europe were part of one single supercontinent called “Laurasia.” When Laurasia broke up and continents began drifting apart, 4-toed eohippus grazed in NA and in England simultaneously for a while before the primitive horse ancestor went extinct in Europe.  |

| 3-toed horse leg bone fossil from SE Arizona |

In the mountains and deserts of (what would become) Mexico and southwestern US, Spanish explorers needed lots of durable horses to search for their mythical cities of gold – not to mention horses that could survive the seven-month sea crossing while hung in slings. So they set up horse breeding rancheros, first in the West Indies and then in Mexico.

While horses gave Conquistadors and missionaries the ability to penetrate inland, the Spanish inadvertently brought horse culture to Native Americans. And horses in turn gave Indians the ability to drive the Spanish out of their homelands for more than a century.

The Spanish issued decrees forbidding natives to own or ride horses. But in 1621, a governor gave permission for Pueblo Indians to work on horseback for the Spaniards. Soon, Apaches and Navajos (whom the Spanish targeted for slavery) were stealing horses from the Pueblo and then from the Spaniards themselves.

During the Rebellion of 1680, the Pueblo tribes drove the Spaniards out of “New Spain” and back into (what would become) Mexico and Texas. The fleeing Spanish left behind thousands of hardy horses – horse stock that would eventually be traded north, tribe-by-tribe, into California, the Rocky Mountains and the Great Plains. Over the years, some of the little Spanish ponies broke for freedom and established large bands of free-ranging horses across much of NA.

The native Indians had to learn horsemanship. But in less than a century, most NA tribes had assimilated horses into their cultures. The span of years between 1640 and 1880 is now referred to as the “Period of Indian Horse Culture.” Nomadic tribes gained power over farming tribes, and the military balance between many tribes was turned upside-down.

Indians generally left the wild horse bands alone, preferring instead to steal trained horses from the rancheros. Comanche Indians were fond of saying that they only allowed the Spaniards to remain in Mexico to provide them with fresh horses.

|

| Three Chiefs Piegan (Blackfeet) in Montana by Edward S. Curtis (public domain photograph) |

Not long after Lewis and Clark, waves of white settlers began flooding west, and their farming lifestyle conflicted with the nomadic hunting lifestyle of many native Indian cultures. To break and subjugate the native peoples, the US turned to the unofficial policy of decimating the buffalo. Their efforts forced most of the Indians onto reservations, but that wasn’t enough. The government decided to also destroy the Indians’ beloved ponies.

In Montana during the early 1920’s, the US government and some large ranchers shot an estimated 50,000 “Indian Ponies” on the Crow Reservation alone, plunging the Crow nation into poverty. Wagonloads of bleached horse bones were carted off to be ground into calcium.

In the mid-1800’s, there were an estimated 2-7 million free roaming horses the western US. Horses were not considered a “problem” until large numbers of sheep and cattle were introduced. By the turn of the century, the wild horse population had fallen to an estimated 1 million.

In 1963, a committee of distinguished scientists was set up to determine which species would be protected as “native” in US wildlife preserves. Their report recommended protection for those species that were present when the first European explorers arrived. Horses were left off the list, even though they were native to the US and had been reported by explorers in the Great Plains in the 1600’s and in the northwest in the 1800’s.

Wild horses were denied any sort of status or protection in the US because they had descended from domesticated Spanish ponies. They were considered “feral,” and they could be legally harassed or shot, or rounded up and hauled off dead or alive to rendering factories. Once again, wild horses were heading towards extinction on their native continent.

Down in the Pryor Mountains, locals learned of plans by the Bureau of Land management (BLM) to remove all wild horses from the range to make room for more cattle and mule deer. The battle came to a head in 1969, when Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall denied the BLM and designated the range as a wild horse refuge.

Straddling Montana and Wyoming, the “Pryor Mountain Wild Horse Range” was born. Genetic testing of horses there proved that they were directly descended from the “Colonial Spanish Horse,” a type of horse that no longer exists in Spain.

In 1971, the BLM estimated that 17,000 wild horses remained. That was the year Congress finally passed the “Wild Free-Roaming Horse and Burro Act” to protect the remaining animals. Horse numbers began to recover, and in 1973 the BLM “Adopt-a-Horse” program began in the Pryor Mountains.

|

| Buffalo Girl keeps a close watch over Kitalpha, her foal. Both are wild and free-living Montana Mustangs. |

Our wildlife management agencies are still under the thumb of corporate ranchers, and hook-and-bullet good ol’ boys. But the tide is slowly turning, and wild animals are starting to be valued for non-consumptive purposes, although a real “wildlife ethic” is still a ways off. For now, Montana’s last wild horses appear to be relatively safe -- just as long as horse advocates keep a close watch over them.

Wild horse advocates:

The Cloud Foundation, Colorado Springs, CO

Wild horse media:

You can watch the Nature special (free online), “Cloud: Wild Stallion of the Rockies,” which tells the story of a Pryor Mountain Stallion.

You can read a fascinating and thoroughly detailed history of “Indian Horse Culture," starting here.

Labels:

Lewis and Clark,

MT History,

Wild Horses

Location:

Crooked Creek Rd, Bridger, Mt 59014, USA

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

The Dogwood Cousins

Sometimes, family get-togethers can try your patience. I was a wee small tyke when someone got the bright idea of gathering together about a dozen of my pre-teen cousins. As I recall, it only happened once.

These funny strangers were part of my family, it was explained, even though they had different last names and arrived in a wide array of sizes, shapes and colors. Over the years, the whole gang of us dispersed around the country, settling into our preferred habitats to sink roots and raise families.

It's a similar story for the dogwood family. The 40 or so different dogwood species that settled in specific habitats across the U.S. also grow in a wide array of sizes, shapes and colors. They have the same first names (Cornus) but different last names.

These funny strangers were part of my family, it was explained, even though they had different last names and arrived in a wide array of sizes, shapes and colors. Over the years, the whole gang of us dispersed around the country, settling into our preferred habitats to sink roots and raise families.

It's a similar story for the dogwood family. The 40 or so different dogwood species that settled in specific habitats across the U.S. also grow in a wide array of sizes, shapes and colors. They have the same first names (Cornus) but different last names.

|

| Multiple stems of one Bunchberry Dogwood plant |

At first glance, you might think these three dogwoods are unrelated. The coastal Pacific Dogwood forms a small tree with lovely, white flowers. Here in Montana, Red-osier Dogwood is a large, colorful shrub, while Bunchberry Dogwood is a wee small forb. But it's a set of very specific characteristics that defines a flora family. For dogwoods, these include botanist-arousing details like, "a lobed calyx that joins the pistol to form a two-seeded fruit." Well, okay.

But there is a characteristic shared by our two Montana natives that also appeals to non-botanists -- the color red. Well, sort of. Red appears in different seasons and on different plant parts, so be patient on this one.

|

| White Red-osier fruit |

Fall is also when Red-osier begins earning its common name, and its keep. The new growth of summer started out red but slowly turned gray-green as it aged. But in fall, the stems turn into bright, eye-catching red. They'll go green again next summer, but these red stems provide some of the only color relief during the long months of cloudy winter white. The red branches appeal to travelling naturalists and other animals that pause to take note of this native.

|

| Red-osier stems and leaves in fall |

At some point during the year, Red-osier Dogwood is also important to many wild animal species. It is browsed by white-tailed deer in spring and mule deer in summer. The white fruits are a key food for both grizzly and black bears in the northern Rockies. This shrub often grows along stream banks, and even cutthroat trout eat the berries that fall into creeks. The burgundy leaves are a fall favorite for moose, and elk seek out the younger stems in winter. A bunch of other animals use Red-osier Dogwood, including rabbits, turkeys, grouse, ducks, ravens and beavers.

Bunchberry Dogwood

Compared to its gangly cousin, our native Bunchberry Dogwood is much shorter and, most of the year, much less colorful. That's because it has the unusual lifestyle (for a dogwood) of a creeping, perennial forb. It tops out at only 6-8 inches tall -- on a warm day.

In mid-summer, Bunchberry sprouts from long-lived rhizomes that lie just a few inches below the surface. It is a clonal plant that survives by growing a cluster of green, above-ground stems each summer for photosynthesis and flowering. In one study, one below-ground rhizome was 172 inches long and more than 36 years old.

The Bunchberry strategy relies more on vegetative regeneration than on seeds. Seedling survival is low due to low fruit set and germination, and slow growth. Three-year-old seedlings are only about 1" tall, and they don't begin growing the all-important rhizomes until after their fourth year.

|

| Summer 's white flower cluster turns to fall's red berry bunch. |

Though short in stature, Bunchberry Dogwood is an important browse plant for mule deer and moose in summer, when it's growing above ground. Grouse eat the early buds while other birds eat the summer fruits. Mice and their kin rely on the fruits each winter.

In summer, each Bunchberry stem grows what looks like one white flower. But this is actually a cluster of many small flowers that are set within four white "bracts," or modified leaves. Bees and flies handle the pollination, and late summer or early fall is when these little dogwoods earn their common name. Each cluster of greenish-white flowers turns into a bunch of bright red berries, or berry bunches, or bunchberries.

So in our dogwood family, the tall Red-osier stems turn bright red during fall, and the short Bunchberry stems grow red berries in late-summer. See? I told you we would eventually tie them together with the color red. You just had to be patient enough to get through a summer and fall with Montana's native dogwood cousins.

Wednesday, June 9, 2010

Historic Horsetail

What can we learn from a family of plants that is 400 million years old? After all, the ancient horsetail (Equisetum spp.) has hardly changed during its long history with dinosaurs, humans and bears. What do we really know about this common native plant?

Equisetum (from the Latin equus "horse" + seta "bristle") is the only living descendant from a group of plants that once dominated the Paleozoic forests. The horsetail family was a successful group long before the rise and fall of dinosaurs. Some of their ancestors lived with early dragonflies that had 2.5 foot wingspans. These ancient horsetails were many of the plants that died and slowly compressed into the coal that we dig up and use today.

Modern day horsetails are smaller, 2" to 14" tall plants that often favor wet areas. There are at least seven species native to Montana.

Most of each horsetail plant lives deep in the ground. A large underground rhizome sprouts two different kinds of above-ground stems: brown and green. Pale brown spore-bearing stems ("strobulus") arise in spring, followed by the familiar green vegetative stems with their wispy whirled branches.

Below the visible stems, underground rhizomes grow more than six feet deep. (This is why pulling, plowing and burning have little or no effect.) At one-foot intervals, the rhizomes branch out sideways and grow food-storing tubers.

Most reproduction is by asexual sprouts from the rhizomes. Horsetails don't produce flowers. For sexual reproduction the horsetail grows brown, spore-bearing stems during May and June.

Most reproduction is by asexual sprouts from the rhizomes. Horsetails don't produce flowers. For sexual reproduction the horsetail grows brown, spore-bearing stems during May and June.

The spore-bearing strobulus is a pale brown cone because it lacks chlorophyll. The tiny spores start out as male and female gametes, but over time the female spores also grow male parts, resulting in male and bisexual gametes. The gametes are less than 0.016 inches tall, only a few cells thick, and short-lived. Male sperm must travel through water to reach an egg-bearing female part, so sexual reproduction is thought to be rare in horsetails.

As the brown cone stems start to shrivel, the familiar green stems begin to elongate. The whirls are actually slender branches, and the tiny leaves have been reduced to small brown scales around the stem.

HUMAN USES

Native Americans also made wide use of horsetail for food and medicine. Crow and Flathead Indians used it as a diuretic, and the Blackfeet boiled it to make cough medicine for horses. Cree and Crow Indians used horsetail to relieve abdominal pains.

Natives and early settlers ate the young horsetail shoots raw or cooked, like asparagus. They also drank a diuretic tea brewed from horsetail, and made green dyes for lodges and clothing.

The rough silica crystals made dried horsetail a favorite tool for scouring and polishing. Settlers gathered bundles of horsetail and used them to scour floors and polish metal, especially pewter. Some Native Americans still use horsetail to polish ceremonial pipes, as well as bows and arrows. Indian children even made whistles from the hollow horsetail stems -- a use that was echoed by early Europeans.

BEARS & HORSE TALES

Green horsetail shoots are 15% protein by dry weight. But eating too much horsetail can be poisonous to its namesake -- horses. While Captain Clark (of Lewis and Clark fame) noted that, "the horses are remarkably fond of it," horsetail can cause paralysis and death in horses. It is seldom eaten by other livestock, and deer and elk avoid it as well.

Bears, on the other hand, love the stuff.

Bears stay alive by eating their vegetables. The most important bear foods are forbs in spring (horsetail, clover, dandelions), ants in summer, and berries in the fall. For most bears, meat is just an occasional bonus. Plants and ants stave off starvation until the bears can fatten up on fall berries.

For Montana's grizzlies, forbs are important throughout the bears' active period. In spring, horsetail is the bears' favorite food across northwestern Montana. In summer, horsetail ranks 10th out of 32 food items eaten by grizzly bears in the southeastern corner we call Yellowstone.

|

| Horsetail growing in water |

Bear diet and habitat use both change with plant availability. Bears start at low elevation sites in spring and follow plant development to higher elevations in summer. In this way, bears eat horsetails that are in their immature, most nutritious stages, relatively higher in soluble nutrients and lower in fiber than mature plants.

LESSONS LEARNED

Horsetail has survived many millions of years longer than humans. These plants managed to hang on during periods of mass extinction and global climate change. In the process, they grew their roots deep and helped their neighbors fend off illness and starvation. Can we learn any lessons from this ancient family?

.

.

Friday, December 25, 2009

Name That Native Plant

|

| Our native forb with a bushell of names |

It's scientific name (from the 1700's) is one of my all-time favorites, Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (ark-toh-STAF-ih-los OO-va ER-see). Those words feel good rolling around in your mouth -- especially the uva-ursi part. And the funny thing is, this name is Greek-Latin double-talk; the first and second words mean the same thing.

The genus, Arctostaphylos, is Greek. Arkto means bear, and staphyle means a bunch of grapes, so this part translates into "bear grapes." The species, uva-ursi, is Latin. Uva means grape and ursi means bear. So when you sing-song Arctostaphylos uva-ursi, you're really saying "bear grapes bear grapes."

Currently, one of the most common names for the plant is kinnininnick, which is an Algonquian (Delaware Indian) word that means "mixture." That's because the dried leaves were often mixed with tobacco to mellow out the flavor and, especially, to make the tobacco supply last longer. Just ask Lewis and Clark.

Their expedition finally reached the Pacific Ocean late in 1805, drenched by non-stop rain and in need of emergency winter shelter. And just as worrisome, their supply of Turkish tobacco was dwindling. So even before their shelter was finished, Captain Clark, "dispatched two men to the open lands near the Ocian for Sackacome, which we make use of to mix with our tobacco to Smoke, which has an agreeable flavour."

|

| Lewis and Clark's very own pressed Uva-ursi specimin |

Earlier, in about 1625, European botanists gave the plant another one of its common names, Bearberry. In 13th century England, medicinal uses for uva-ursi leaves were described in the "The Physicians of Myddfia," a Welsh Herbal ("Herbals" are books of plant medicinal uses). But -- as you might have guessed -- many of the old Herbals had another name for this plant, Arbutus.

Whatever name you might know it by, this short heather has a long history.

|

| Uva-ursi berry under snow in winter |

But the red berries taste rather mealy to many people, including Meriwether Lewis. "The natives on this [the west] side of the Rocky mountains who can procure this berry invariably use it. To me it is a very tasteless and insippid fruit," he wrote. Native Americans fried or boiled the fruit, which is high in vitamin C, to make them a little sweeter. They also mixed the berries with fat and dried buffalo meat to make pemmican (a method invented by Native Americans to store surplus food for future need).

Dried uva-ursi leaves were often mixed with tobacco, and they were also smoked instead of tobacco. One traditional tobacco-substitute recipe that was smoked in the northwest consisted of equal parts dried leaves of uva-ursi, bayberry, Labrador tea, and wormwood mixed with the inner bark of red osier dogwood, chokecherry and alder.

|

| Uva-ursi berries in summer |

Modern-day herbalists still use uva-ursi. The dried leaves contain arbutin and tannic acid. Arbutin is an astringent with antiseptic properties, and it is useful for killing bacteria in the urine. And tannic acid from uva-ursi is used commercially in Scandinavia for tanning leather hides.

Of course, Scandinavians have their own names for this little heather. They include: mjølbær (Norwegian), hede-melbærris (Danish), sianpuolukka (Finnish), and grainnseag (Gaelic).

Here in Montana, the Salish name for bearberry is skw lsé, and the Blackfeet call it kakahsiin.

Just don't ask me how to pronounce any of those names. My head's still spinning a little, so I'll just stick with my favorite, Arctostaphylos uva-ursi. Now didn't that just feel good rolling off your tongue?

|

| Kinnikinnick flowers in spring |

Sunday, December 13, 2009

The Rocky Mountain Locust

After the last ice age, the land we now call Montana was shaped by the presence of -- and is now reshaping in the absence of -- a number of landscape-wide influences.

Lightning strikes set patches of forests and prairies afire at frequent intervals for almost 10,000 years. And for centuries, Native Americans lit grass fires regularly to expand and maintain the prairies, which helped the fire-adapted native grasses thrive and feed their main source of food, the massive bison herds.

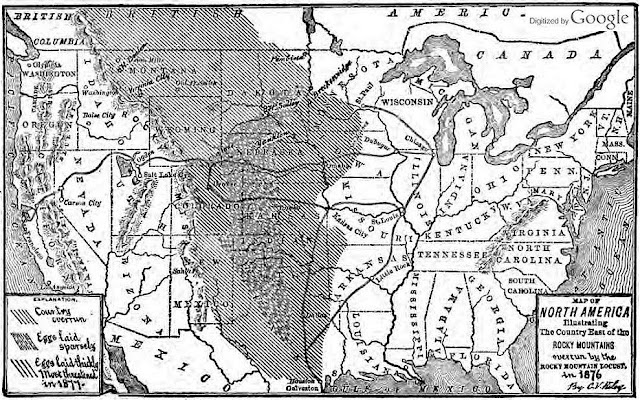

And in addition to the frequent fires, native peoples, and millions of bison, there was one prairie insect whose influence was also felt landscape-wide -- the inch and one-third long, Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus).

And in addition to the frequent fires, native peoples, and millions of bison, there was one prairie insect whose influence was also felt landscape-wide -- the inch and one-third long, Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus).

The Guinness Book of World Records lists locust swarms as the "greatest concentration of animals." One swarm covered 198,000 square miles -- Montana is a little over 147,000 square miles. Europeans settling in the Montana Territory endured repeated locust swarms, which peaked in the pre-statehood years between 1873 and 1877.

And then, in less than 25 years, North America's only major locust suddenly vanished. Everywhere. "The First Annual Report of the State Entomologist of Montana" in 1903 declared that Rocky Mountain Locusts, "...if present in the state at all is very rare." They had no way of knowing that the last living locust had died a year earlier.

What happened?

Summer 1868. A locust swarm in the vicinity of Helena, "came in from the north, ...striking the buildings on the south side of the street, and fell down in such large numbers as to form 'drifts of 'hoppers.'" One man in Helena said there were so many locusts that, "... while driving oxen he 'couldn't see the front yoke.''

March 1877. The U.S. Entomological Commission was created to "...prevent this fertile country from being overrun by the disastrous winged swarms from the Northwest."

August 1878. A company of army troops moving through Milk River area reported, "...the appearance of vast swarms of locusts... coming and going for more than one week. ...Some of the men with whom I spoke say that the roar of their wings was much like the sound of a tornado."

August 1879. The U.S. Entomological Commission reported, "During the summers of 1874, 1875, as well as 1878, the locusts were so numerous at Bozeman that they entered stores and eat [sic] holes in the various kinds of goods."

Spring 1887. In the Sun River Valley, "the young [locusts] were so numerous that the ground was completely hidden by them in many localities."

Settlers flooded westward only to find unpredictable waves of locusts swarming east and south -- and a battle for the Great Plains was set into motion. Hungry locusts devoured almost all vegetation in their path, including many of Montana's first fields of wheat and grains. (Oddly, they avoided tomatoes, raspberries, and alfalfa.) They also ate fence posts, clothing, bark, leather, and wool still on the sheep.

Settlers flooded westward only to find unpredictable waves of locusts swarming east and south -- and a battle for the Great Plains was set into motion. Hungry locusts devoured almost all vegetation in their path, including many of Montana's first fields of wheat and grains. (Oddly, they avoided tomatoes, raspberries, and alfalfa.) They also ate fence posts, clothing, bark, leather, and wool still on the sheep.

But then suddenly, at the turn of the century, locusts vanished for mysterious reasons. One hundred years later, in 2004, a Wyoming scientist finally put the clues together and solved the cold case of the disappearing locusts.

Farmers moved in and unknowingly (at first) began plowing these same locust core areas for their crops.

Farmers moved in and unknowingly (at first) began plowing these same locust core areas for their crops.

The 50,000 farmers of 1890 had the capacity to plow 5% of the locusts' core breeding grounds in just one day. It didn't take long. Breeding grounds were converted into farmland and pasture, and the insects never recovered.

Native locusts were driven to extinction. Bison narrowly avoided the same fate. Native Americans were intentionally starved and forced onto reservations. Wild fires were fought with little regard for their beneficial effects. And underneath it all, the native prairies were reduced to isolated patches that total less than 1% of what once existed.

But today, the Rocky Mountain Locust is rising once again -- sort of.

In the Beartooth Mountains of southwestern Montana, there lies the remains of the aptly-named "Grasshopper Glacier." (Actually, there are two "Grasshopper Glaciers" and one "Hopper Glacier.") Apparently, when swarms of the migratory locusts flew over the mountain range, many were caught in storms or otherwise perished, and were buried in accumulating snow and ice.

"Grasshopper Glacier" was four miles long in 1914, but now it's only one-quarter of that size. Thanks to the effects of global warming, melting ice is now slowly revealing its cache of millions of long-dead locusts that lived in decades past.

Read more: Why locusts swarm

Behind the bug: You can read all about the Rocky Mountain Locust in professor Jeffrey Alan Lockwood's book, "Locust: The Devestating Rise and Mysterious Disappearance of the Insect That Shaped the American Frontier." If you're into 500+ page government reports, you can download the "Third Report of the United States Entomological Commission" (the most interesting one) at: http://books.google.com/books.

Lightning strikes set patches of forests and prairies afire at frequent intervals for almost 10,000 years. And for centuries, Native Americans lit grass fires regularly to expand and maintain the prairies, which helped the fire-adapted native grasses thrive and feed their main source of food, the massive bison herds.

And in addition to the frequent fires, native peoples, and millions of bison, there was one prairie insect whose influence was also felt landscape-wide -- the inch and one-third long, Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus).

And in addition to the frequent fires, native peoples, and millions of bison, there was one prairie insect whose influence was also felt landscape-wide -- the inch and one-third long, Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus).

The difference between grasshoppers and locusts is behavior. When they occur in non-damaging, non-migrating, low-density, widespread populations, they are grasshoppers. They are locusts when they form damaging, concentrated, migratory populations.

When Lewis and Clark were migrating across the northwest, there were roughly 30-60 million bison in North America. Seventy years later, the locust population was peaking at around 15 trillion insects at the same time that those 11 million tons of bison were getting slaughtered by commercial hunters and government agents. Soon, at 8.5 million tons, locusts outweighed bison.

The Guinness Book of World Records lists locust swarms as the "greatest concentration of animals." One swarm covered 198,000 square miles -- Montana is a little over 147,000 square miles. Europeans settling in the Montana Territory endured repeated locust swarms, which peaked in the pre-statehood years between 1873 and 1877.

And then, in less than 25 years, North America's only major locust suddenly vanished. Everywhere. "The First Annual Report of the State Entomologist of Montana" in 1903 declared that Rocky Mountain Locusts, "...if present in the state at all is very rare." They had no way of knowing that the last living locust had died a year earlier.

What happened?

Summer 1868. A locust swarm in the vicinity of Helena, "came in from the north, ...striking the buildings on the south side of the street, and fell down in such large numbers as to form 'drifts of 'hoppers.'" One man in Helena said there were so many locusts that, "... while driving oxen he 'couldn't see the front yoke.''

March 1877. The U.S. Entomological Commission was created to "...prevent this fertile country from being overrun by the disastrous winged swarms from the Northwest."

August 1878. A company of army troops moving through Milk River area reported, "...the appearance of vast swarms of locusts... coming and going for more than one week. ...Some of the men with whom I spoke say that the roar of their wings was much like the sound of a tornado."

August 1879. The U.S. Entomological Commission reported, "During the summers of 1874, 1875, as well as 1878, the locusts were so numerous at Bozeman that they entered stores and eat [sic] holes in the various kinds of goods."

Spring 1887. In the Sun River Valley, "the young [locusts] were so numerous that the ground was completely hidden by them in many localities."

Settlers flooded westward only to find unpredictable waves of locusts swarming east and south -- and a battle for the Great Plains was set into motion. Hungry locusts devoured almost all vegetation in their path, including many of Montana's first fields of wheat and grains. (Oddly, they avoided tomatoes, raspberries, and alfalfa.) They also ate fence posts, clothing, bark, leather, and wool still on the sheep.

Settlers flooded westward only to find unpredictable waves of locusts swarming east and south -- and a battle for the Great Plains was set into motion. Hungry locusts devoured almost all vegetation in their path, including many of Montana's first fields of wheat and grains. (Oddly, they avoided tomatoes, raspberries, and alfalfa.) They also ate fence posts, clothing, bark, leather, and wool still on the sheep.

Starving settlers fought back by burning, poisoning and flooding -- all to little success. Religious leaders proclaimed that the locusts were sent to punish settlers for their sins, and they prayed and performed exorcisms to banish the insects -- also to little success. Locust swarms tormented the settlers for more than 30 years.

But then suddenly, at the turn of the century, locusts vanished for mysterious reasons. One hundred years later, in 2004, a Wyoming scientist finally put the clues together and solved the cold case of the disappearing locusts.

Locusts were quickly plowed into extinction -- literally -- when western farming practices collided head-on with the insect's own natural history.

The Rocky Mountain Locust swarms were occasional and erratic. Between irruptions, the population fell back to much smaller levels -- perhaps as few as 10 million locusts -- in areas along the eastern flanks of the Rocky Mountains. While great swarms afflicted the prairies, the core population existed almost exclusively in arable lands along streams -- land that was good for farming.

Farmers moved in and unknowingly (at first) began plowing these same locust core areas for their crops.

Farmers moved in and unknowingly (at first) began plowing these same locust core areas for their crops.

Reports of farmers finding locust eggs by the thousands were common. When they turned the soil, they exposed the buried locust eggs to Montana's freezing temperatures. When surviving eggs hatched upside-down in the sod, many hatchlings were too deep to surface and too small to negotiate the broken clumps. And when farmers started planting alfalfa, which requires a lot of water, they grew a non-native crop that was apparently not eaten by locusts, and one that created a moist habitat where locusts could not survive.

Native locusts were driven to extinction. Bison narrowly avoided the same fate. Native Americans were intentionally starved and forced onto reservations. Wild fires were fought with little regard for their beneficial effects. And underneath it all, the native prairies were reduced to isolated patches that total less than 1% of what once existed.

But today, the Rocky Mountain Locust is rising once again -- sort of.

In the Beartooth Mountains of southwestern Montana, there lies the remains of the aptly-named "Grasshopper Glacier." (Actually, there are two "Grasshopper Glaciers" and one "Hopper Glacier.") Apparently, when swarms of the migratory locusts flew over the mountain range, many were caught in storms or otherwise perished, and were buried in accumulating snow and ice.

"Grasshopper Glacier" was four miles long in 1914, but now it's only one-quarter of that size. Thanks to the effects of global warming, melting ice is now slowly revealing its cache of millions of long-dead locusts that lived in decades past.

Read more: Why locusts swarm

Behind the bug: You can read all about the Rocky Mountain Locust in professor Jeffrey Alan Lockwood's book, "Locust: The Devestating Rise and Mysterious Disappearance of the Insect That Shaped the American Frontier." If you're into 500+ page government reports, you can download the "Third Report of the United States Entomological Commission" (the most interesting one) at: http://books.google.com/books.

Tuesday, August 11, 2009

The Wild Lupine

Lupines are members of the pea family that will hybridize with each other in order to keep the taxonomists busy. Montana currently claims about 12 of the 80 or so species/sub-species/varieties argued over by modern-day botanists. Silky lupine (Lupinus sericeus) is probably the most common member here in our state.

Lupines grow as bushy forbs, and they are valuable as food and cover for wildlife. White-tailed deer, upland game birds, some non-game birds, and Columbian ground squirrels all dine on lupine. In Glacier National Park, bighorn sheep seek out the dried lupine stalks for winter forage. But for domestic sheep, lupine can be tasty or fatal, depending on the time of year.

Let me see, I believe it was late-June back in 1900, when those greenhorn sheepherders started driving some 6,000 imported sheep across the belly of Montana. (Yep, I'm older than I look.) You should'a seen them unload those wooly buggers, one train load after another. Five miles out from the old Livingston stockyards, these ol' boys split the sheep into two bands and settled in to camp for the night on opposite sides of a small "crik." By morning, most of the sheep in one band showed signs of poisoning. Within three days, 1,900 sheep had died -- all from the north band.

Suspicions were cast on an enemy of the sheep owner, but post-mortem exams showed that all of the dead sheep had large amounts of lupine seeds and pods in their stomachs. Lupine grew in great numbers on the north side of the creek, but not on the south side. The non-native sheep had been driven a hard five miles and were ravenous when they reached the creek -- and the ripened, native lupines.

Ripe lupine seeds contain alkaloids, which are bad news for most domestic animals. Ranchers these days know to avoid lupines in the summer, until after the seeds have fallen out of the pods.

The genus, Lupinus, comes from the Latin word for wolf, lupus. Many explanations exist for how this name became attached to this group of plants. My favorite is rooted in the legend of a she wolf that discovered Romulus and Remus -- abandoned and left floating in a pod -- and how she nursed them back to health. In a similar vein, lupine plants nurture the soil for other plants by taking nitrogen from the air and fixing it in their roots. The ability to add nitrogen to the soil, and colonize low-fertility soils, makes lupine valuable for rehabilitating disturbed areas like abandoned mine sites.

As natives, lupine species are also well-adapted to the wildfires that are a natural part of our intermountain ecology. After a fire passes through, individual plants re-sprout from a below-ground stem (the "caudex"), and buried seeds sprout profusely. The result is that lupine stands often increase in size and density after a fire. Forest floors and dry hillsides swept clean by wildfires will often turn into that familiar carpet of blue wildflowers that Lewis and Clark enjoyed.

There's one more reason, I think, that lupines look so familiar. If you closely examine just one of the many flowers on a stalk -- maybe squint a little -- you just might see the face of a famous television and movie star.

There's one more reason, I think, that lupines look so familiar. If you closely examine just one of the many flowers on a stalk -- maybe squint a little -- you just might see the face of a famous television and movie star. It's Pluto, Micky Mouse's faithful dog! From his black nose to his white eyes, the only things missing are Pluto's ears.